Life-Changing Lessons from A Thousand Splendid Suns

When I first encountered this book years ago, I was struck by its emotional resonance; returning to it now, I am humbled by its philosophical depth.

Hosseini has accomplished something rare in modern storytelling – a narrative that refuses both saccharine sentimentality and fashionable nihilism in favor of a more difficult truth: that meaning persists even in seemingly meaningless suffering, that beauty coexists with brutality, that small acts of human decency can counterbalance monumental structures of oppression.

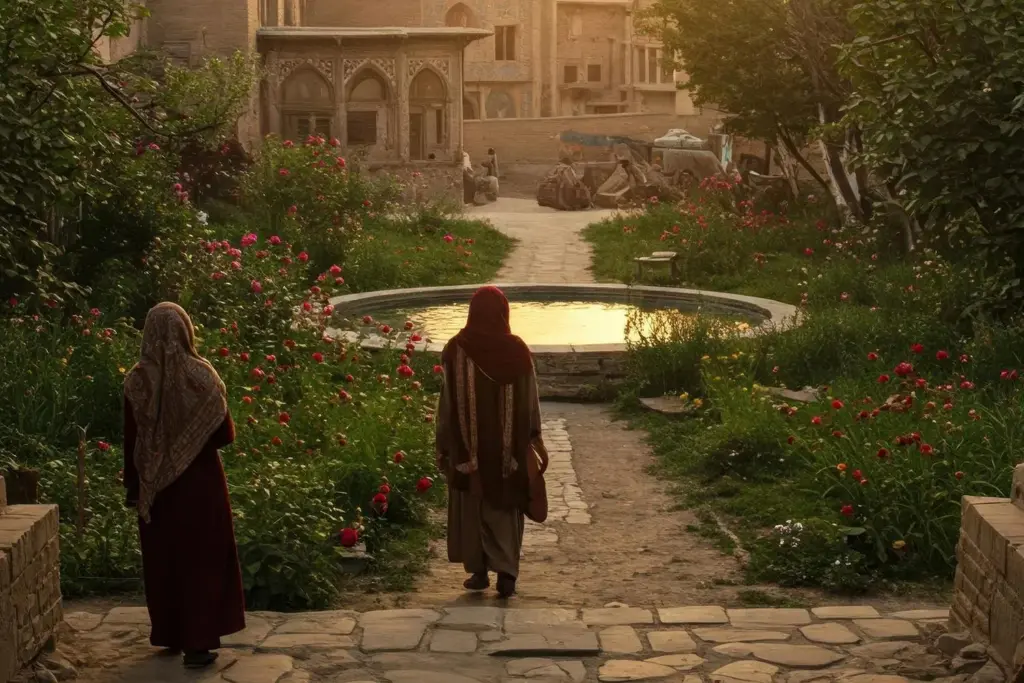

Through the intertwined fates of Mariam and Laila – two women separated by generation but united by circumstance in war-torn Afghanistan – Hosseini offers us not just a compelling story but a sustained meditation on how we navigate the tension between determinism and agency, between the circumstances we inherit and the choices we make within their constraints.

Their journey becomes a microcosm for our universal struggle to maintain dignity when external conditions conspire to strip it away.

Life-Changing Lessons from A Thousand Splendid Suns

1. Being Seen Matters

The most profound achievement of Hosseini’s narrative lies in its insistence on rendering visible what typically remains unseen.

Mariam’s existence as a harami (illegitimate child) condemns her to social invisibility, yet through her eyes, we witness an entire hidden history – the private lives of Afghan women whose experiences rarely enter official records.

“She would never leave her mark on Jalil’s world. She would leave no evidence that she had existed. Her suffering would become one more thing that would be forgotten.”

This early passage establishes invisibility as Mariam’s greatest fear, yet the novel itself becomes the counterargument to this despair.

By witnessing Mariam’s life in its fullness – her sorrows and small joys, her quiet rebellions and final sacrifice – Hosseini performs a kind of literary justice, suggesting that attention itself constitutes a moral act.

In an age where visibility often becomes confused with significance, the novel reminds us that the most consequential lives are frequently lived beyond the spotlight, and that bearing witness to unwitnessed lives might be our highest calling.

2. Women Supporting Women Changes Everything

The relationship between Mariam and Laila evolves from initial hostility to profound connection through a sequence of small gestures that accumulate into something revolutionary.

Their bond becomes not just personal salvation but political resistance – a microcosm of how women’s solidarity can undermine patriarchal structures from within.

“Women like us. We endure. It’s all we have.”

This statement, uttered by Mariam, initially sounds like resignation but gradually reveals itself as a philosophy of resistance.

The women’s shared endurance – their quiet conspiracies and protected secrets, their division of household labor and collective childcare – creates an alternative economy of care within the brutal household economy controlled by Rasheed.

Hosseini thus illuminates how women’s relationships can function as counterculture, creating spaces of reciprocity within structures of exploitation.

This lesson feels particularly resonant in our present moment, when women’s collective action continues to challenge entrenched power across cultural contexts.

3. Beauty Survives Alongside Suffering

Even in depicting Afghanistan’s most harrowing historical moments, Hosseini maintains an attentive eye for beauty that refuses simplistic categorization as either war-torn wasteland or exotic paradise.

The novel’s title itself, drawn from a 17th-century poem praising Kabul, insists on this complexity:

“One could not count the moons that shimmer on her roofs, Or the thousand splendid suns that hide behind her walls.”

This poetic image captures the novel’s aesthetic philosophy – that beauty persists not despite destruction but alongside it, hidden yet present, requiring only the right kind of attention to perceive.

When Laila later returns to Afghanistan after years in exile, she acknowledges this contradictory reality:

“She has found her way back to the place of thin air and scorching summers and diesel fuel and gun smoke… But also of bread baking in tandoor, and the call to prayer, and snow-capped mountains, and buzkashi tournaments, and children flying kites…”

This balanced inventory neither minimizes suffering nor romanticizes hardship, instead modeling a mature engagement with place that acknowledges its multiple, simultaneous truths.

In a global discourse often dominated by one-dimensional representations of conflict zones, this insistence on complexity constitutes a significant ethical stance.

4. Motherhood Is Quiet Heroism

Motherhood in A Thousand Splendid Suns emerges as both biological relationship and moral choice, embodied in multiple forms: Nana’s bitter devotion, Mariam’s surrogate maternity, Laila’s fierce protectiveness.

What unites these diverse expressions is a commitment to shielding vulnerability in a world designed to exploit it.

“Of all the hardships a person had to face, none was more punishing than the simple act of waiting.”

This observation, reflecting Laila’s anguish while separated from her daughter Aziza, identifies the peculiar suffering of maternal waiting – the helpless interval between worry and resolution.

Yet the novel suggests that this very capacity to bear anxiety for another’s sake constitutes a form of moral courage distinct from more celebrated forms of heroism.

Particularly moving is Mariam’s evolution from childless woman to maternal figure, demonstrating motherhood as stance toward vulnerability rather than merely biological function – a lesson with profound implications for how we might expand our conception of care beyond conventional family structures.

5. Protection Often Masks Control

Through Rasheed’s character, Hosseini delivers a nuanced critique of patriarchal logics that promise protection while delivering control.

Initially presenting himself as Mariam’s savior from disgrace and later as the guardian of Laila’s honor, Rasheed exemplifies how the language of protection often disguises the reality of possession.

“What’s the sense in schooling a girl? It’s like shining a spittoon. There is only one skill a woman like you and Mariam needs to know, and they teach it to you free of charge at home.”

This statement reveals the circular reasoning that justifies women’s dependency by first ensuring their lack of alternatives.

The novel thus exposes the structural violence underlying seemingly individual arrangements – how social systems create the very vulnerabilities they then claim to protect women from.

This lesson extends beyond the specific cultural context to illuminate patterns of gender inequality replicated across diverse societies, challenging readers to recognize similar dynamics in their own environments rather than locating oppression safely elsewhere.

6. Sometimes Breaking Rules Is Necessary

In the novel’s most wrenching scene, Mariam commits an act of violence that costs her life but saves Laila and her children.

This moment confronts readers with the uncomfortable possibility that adherence to moral prohibitions against violence may sometimes perpetuate greater harms.

“Mariam wished for so much in those final moments. Yet as she closed her eyes, it was not regret any longer but a sensation of abundant peace that washed over her.”

This passage transforms Mariam’s violent act into a form of transcendence, suggesting that moral action sometimes requires breaking moral codes – a philosophical problem as old as Antigone’s dilemma.

Rather than glorifying violence, however, Hosseini frames it as tragic necessity within a system that offers no nonviolent paths to justice, challenging both pacifist absolutism and casual acceptance of violence with equal rigor.

This ethical complexity honors readers’ capacity for moral reasoning beyond simplistic prescriptions.

7. Education Changes Everything

Throughout the narrative, access to knowledge functions as both liberation and threat, explaining why controlling regimes target education first.

Laila’s father articulates this connection explicitly:

“A society has no chance of success if its women are uneducated. No chance.”

This statement identifies education not merely as individual advantage but as collective necessity – a perspective reinforced when Laila eventually returns to Afghanistan to teach.

Her insistence that “I’m going to teach. As soon as I can, I’m going to teach” represents not just personal ambition but political commitment to rebuilding a society through the multiplication of knowledge.

In an era when education access remains profoundly unequal globally, the novel reminds us that learning constitutes not luxury but necessity – the foundation upon which all other forms of liberation depend.

8. Fate Is Not Fixed

Both protagonists struggle against fatalistic worldviews that would render their choices meaningless.

While Mariam initially accepts the limitations imposed by her birth status, and Laila later confronts the Taliban’s deterministic interpretation of religious law, both ultimately affirm human agency even within severely constrained circumstances.

“Learn this now and learn it well, my daughter: Like a compass needle that points north, a man’s accusing finger always finds a woman. Always.”

This cynical warning from Nana to young Mariam presents gender injustice as inevitable natural law.

The novel’s trajectory, however, challenges such fatalism without denying the reality of systemic inequality.

This rejection of determinism – whether cultural, religious, or biological – constitutes the narrative’s most hopeful assertion: that even within oppressive structures, meaningful choice remains possible.

This philosophical stance offers neither naive optimism about easy change nor comfortable despair that excuses inaction, but rather a call to what Rebecca Solnit has termed “hope in the dark” – the commitment to act despite uncertain outcomes.

9. Witnessing Pain Has Purpose

Hosseini’s narrative choices – particularly his unflinching depiction of domestic abuse and wartime atrocities – embody an ethical commitment to bearing witness to suffering that might otherwise remain invisible.

This witnessing extends beyond passive observation to active engagement with uncomfortable truths.

“And the past held only this wisdom: that love was a damaging mistake, and its accomplice, hope, a treacherous illusion.”

This passage acknowledges the self-protective appeal of cynicism while the novel as whole refutes it, suggesting that maintaining hope despite evidence of its futility represents a form of moral courage.

In refusing to look away from either suffering or redemption, Hosseini models an ethical stance that rejects both naive optimism and comfortable despair in favor of clear-eyed engagement with reality in all its contradictions – a stance particularly valuable in our era of information overload and compassion fatigue.

10. Meaningful Work Brings Dignity

Throughout the novel, characters’ relationship to work shapes their sense of purpose and worth.

Laila’s eventual role as a teacher represents not merely employment but vocation, while her earlier confinement to domestic labor under Taliban rule illustrates how the denial of meaningful work constitutes a form of spiritual imprisonment.

“She missed the classroom. Sometimes, she dreamed she was standing at the blackboard again… And faces looking up at her with open, earnest expressions, eager to learn.”

This passage connects personal fulfillment to social contribution, suggesting that meaningful work provides not just material sustenance but existential purpose.

In elevating teaching – a profession often undervalued in materialistic societies – to an aspiration worth risking everything for, Hosseini challenges prevailing narratives that measure work’s value primarily in economic terms, offering instead a vision of labor as expression of human capacity to create meaning.

11. We Inherit Both Wounds and Strength

Through three generations of women, Hosseini traces how trauma is transmitted alongside the capacity to endure it.

Laila’s childhood, marked by loss and displacement, echoes aspects of Mariam’s early experiences, while her daughter Aziza inherits both their struggles and their strength.

“People… they noticed that she limped a little, dragged her left leg ever so slightly. But they didn’t notice that she’d lost two brothers, that her father had collapsed on her bedroom floor with a bullet to the head. They didn’t know that she’d endured an afternoon of agony with her mother on the kitchen floor.”

This passage identifies the invisibility of psychological wounds compared to physical ones, highlighting how trauma enters the body’s memory even when absent from public recognition.

Yet alongside this inheritance of pain runs a parallel transmission of resilience, suggesting that what we receive from those before us includes both wounds and the capacity to heal them – a complex legacy that neither romantic narratives of overcoming nor deterministic accounts of damage fully capture.

12. Running Away Doesn’t Solve Everything

The novel complicates simplistic narratives of refugee experience that present escape as unambiguous salvation.

When Laila and Tariq flee to Pakistan, they discover that geographic displacement brings its own forms of loss and displacement.

“She missed the streets of her childhood… But most of all, she missed Mariam.”

This acknowledgment of homesickness amid safety challenges binary framings of exile as either unqualified liberation or mere victimization.

Later, their return to Afghanistan similarly resists easy categorization as either homecoming triumph or foolish risk, instead presenting repatriation as complex moral choice rather than sentimental inevitability.

In an era of unprecedented global displacement, this nuanced depiction offers valuable perspective on migration as neither simple solution nor absolute rupture but ongoing negotiation between safety and belonging.

13. Some Debts Can Only Be Paid Forward

Throughout the narrative, characters accumulate obligations that cannot be discharged through conventional means.

Mariam bears the weight of her mother’s sacrifice and death; Laila carries the burden of surviving when childhood friends did not; both women become indebted to each other in ways that transcend transaction.

“She was leaving it as a friend, a companion, a guardian. A mother. A person of consequence at last.”

This reflection, occurring in Mariam’s final moments, transforms debt into gift – her sacrifice becomes not obligation fulfilled but meaning created.

This reframing challenges predominant economic metaphors that reduce human relationships to exchange value, offering instead a vision of moral economy based on recognition that some debts can never be repaid but only passed forward.

This lesson bears particular relevance in our current climate crisis, where responsibilities toward future generations require similar recognition of asymmetrical obligation.

14. Love Takes Many Forms

While the novel includes elements of romantic love between Laila and Tariq, it places equal emphasis on loves that receive less literary attention: the love between friends, between mothers and children both biological and chosen, between people and places that have wounded them.

These varied manifestations suggest love not as singular emotion but as orientation toward others’ welfare.

“In the coming days and weeks, Laila would scramble frantically to commit it all to memory, what happened next. Like an art lover running through a burning museum, she would grab whatever she could – a look, a whisper, a moan – to salvage from perishing, to preserve. But time is the most unforgiving of fires, and she couldn’t, in the end, save it all.”

This extended metaphor capturing Laila’s attempt to preserve memories of her family transforms love into act of witness – not passive feeling but active attention.

Particularly significant is how female friendship between Mariam and Laila ultimately outweighs romantic attachment in narrative importance, challenging literary conventions that privilege heterosexual romance as life’s defining relationship.

This expanded vision of love’s territories offers liberation from restrictive scripts about which connections merit recognition.

The Continuing Relevance of Hosseini’s Vision Today

What renders A Thousand Splendid Suns particularly significant today is its refusal of both cynical detachment and sentimental simplification in favor of what we might call radical attention – the commitment to see clearly without surrendering compassion.

At a time when public discourse increasingly gravitates toward either performative outrage or comfortable disengagement, this balanced stance offers a model for ethical engagement with complex realities.

The novel’s most radical proposition may be that no life – however constrained by circumstance, however invisible to history’s official record – is without significance.

Mariam, born unwanted and dying under official condemnation, nevertheless transforms her existence into one “of consequence” through choices that ripple beyond her individual fate.

This quiet insistence on the value of seemingly inconsequential lives challenges contemporary value systems that measure worth through public recognition or material acquisition.

“And Mariam thought of her entry into this world, the harami child of a lowly villager… a weed. And yet she was leaving the world as a woman who had loved and been loved back. She was leaving it as a friend, a companion, a guardian. A mother. A person of consequence at last.”

In this final transformation of Mariam’s self-understanding from “weed” to “person of consequence,” Hosseini offers his most profound insight: that our significance derives not from what we achieve but from how faithfully we love – a counter-cultural wisdom that explains why this story continues to resonate so deeply with readers across vastly different life circumstances.

To encounter A Thousand Splendid Suns is to be changed by it – not through dramatic epiphany but through the slow erosion of comfortable certainties about justice, love, and human capacity.

It accomplishes what only the finest literature can: it leaves us more attuned to both suffering and beauty, more aware of our complicity and capacity, more committed to seeing what would prefer to remain unseen.

In short, it leaves us more fully human – and in our world of increasing mechanization, algorithmization, and abstraction, this return to embodied humanity may be precisely what we most urgently need.

Title: A Thousand Splendid Suns

Author: Khaled Hosseini

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Publication Date: May 22, 2007

Pages: 384

Genre: Literary Fiction, Historical Fiction

Setting: Afghanistan (1960s-2000s)

Primary Themes: Female friendship, survival under oppression, motherhood, war’s impact on civilian life

Structure: Third-person narrative alternating between Mariam and Laila’s perspectives

Notable Literary Devices: Historical parallelism, symbolism (particularly the recurring motifs of windows and confinement), foreshadowing

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5)